Boy Prisoners

Boy Prisoners of the Japanese

Boy prisoners in the Japanese internment camps suffered grievously. Many who survived never were able to function normally as adults. The topic has been sadly neglected in literature dealing with the war.

Under Japanese military regulations any male over ten years old was considered an adult. For reasons that are not clear this regulation was applied with particular severity on Java, and the consequences were traumatic. In places such as Shanghai and Hong Kong this did not occur.

Whereas adults had prewar experience of normal life that gave them a moral and emotional anchor, these boys were thrust at an impressionable age into an impossible and often brutal environment. Not only had the war interrupted their education, but it had also distorted their personal development. The consequences frequently were post war distress, manifested in failed marriages, inability to adjust to civilian life, alcoholism , or worse, suicide.

During my own internment period, I began to fear the day I would become ten years old, for that meant leaving the care and security of my mother. I of course, had no idea what such an experience would mean for me, and that may have been just as well because the truth of what happened to these youngsters defies belief. I nevertheless suffered from nightmares for some years after the war.

Some of those who survived the Boys camp experience never fully recovered from the psychological damage.

One of the best written accounts by a camp survivor in English is that of John Stutterheim, who kept a secret diary and therefore provides fresh details of his life in one of the boys camps in central java. Also noteworthy is the book of recollections by Ralph Ockerse , co authored with his sister, Evelijn Blaney.

I was lucky and celebrated my tenth birthday after the war.

Boy Prisoners in Tjimahi

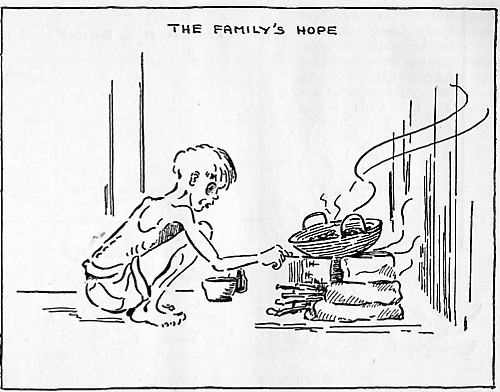

Mr. Hartley (Myn Kamp, niet door Hilter) who drew this cartoon of one such pathetic youngster who happened to be one of the prisoners in Tjimahi, a Men’s camp where my father also was, gave the experience a bitter twist. My father took under his wing one such young lad. After the war he lost contact with Peter, and then miraculously encountered this person forty years later in Vancouver. My younger brother, Peter , born in 1952, was named after my father’s war-time protege.

His caption reads: Many a mothers’ heart would have swelled with pride had she been able to see her dear son’s culinary achievements. It was not just that the raw materials had been obtained via devious means, but the provision of fuel would likely have involved even less elegant techniques: chairs, tables, windows, wooden shoes, all sacrificed for a meal.

Leave a Reply